By and large people hate, hate, hate new ideas at work. New means different. Different means change. Change means work. Uncertainty. New things to argue about. And cuts. No matter what anyone says, cuts always threaten to follow new. Especially in big business.

It doesn’t help that new is almost always championed by someone crazy. Even Geoffrey Moore in his seminal Chasm theory work couldn’t help but describe the innovators who spark every revolution as, well, off their rockers.

These folks, he pointed out, are the first to get on board with a new idea. They don’t care about features that don’t work—they regard faults as a leading indicator of ambition. For early adopters, flaws symbolize vision not sloppy design. Innovators know revolutions are hard, thus revolutionizing they argue, is not for snowflakes. No surprise then that the ones we do credit with creating massive change—Karl Marx, Steve Jobs, Henry IIX, Caesar, Luther (the cleric not the detective, silly), Brando, Napoleon—were also a giant pain in the ass.

Workers long ago learned to run from change as if their lives depended on it. And who can blame them?

You know this. As a Marketer your success depends on your ability to get people to accept the new. Embrace change. Back it with so much enthusiasm that they devour everything you give them about your initiative and scream the benefits from the rooftops.

It’s called Marketing and yes, it’s quite unnatural.

This is a central premise of our work at Mortar: nowhere is the desire to resist change more ingrained, powerful and destructive than to the output from Marketing. And that’s important because most thinkers about brand marketing — on the agency and client side— persistently ignore the challenge of how.

Let’s consider how this applies to the Brand Architecture.

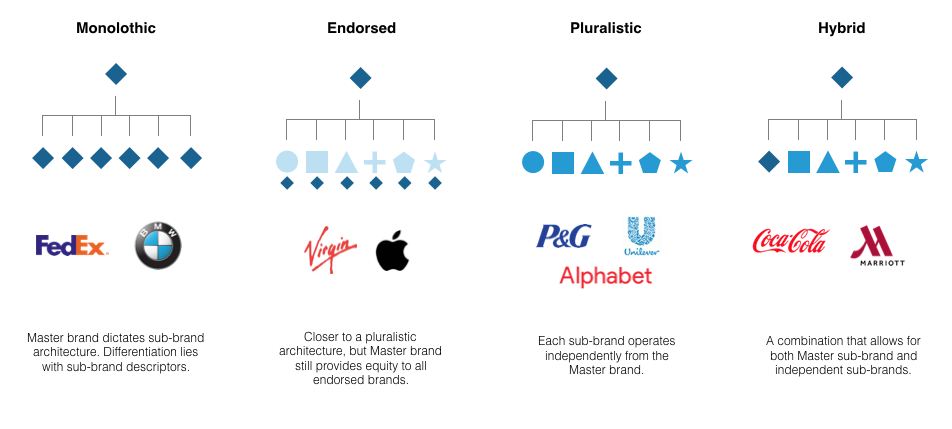

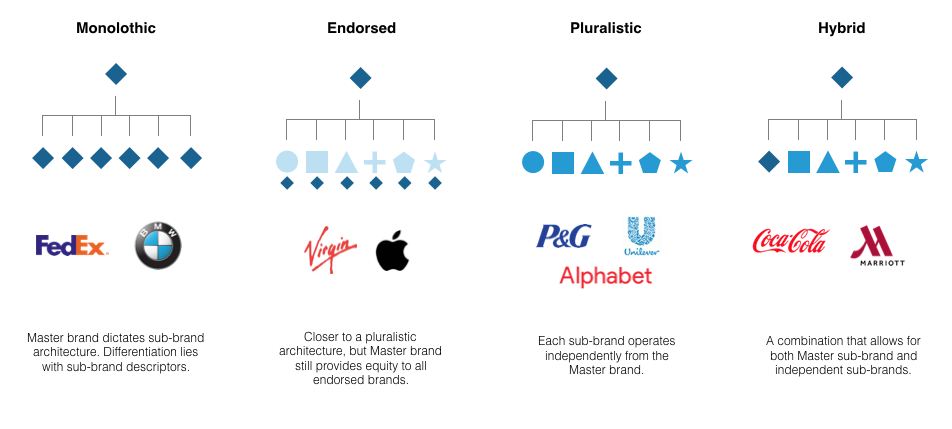

Wikimedia defines Brand Architecture as “the structure of brands within an organizational entity”.

Computer away a little more, and you will find multiple pundits describing the common forms of brand organization. The models are free and widely available. What is striking is how little the experts address the how: how do you take an organization that has grown up working with a range of products and change how it thinks about those products and their relationship to one another and their customers?

Ok so you have the models to follow. Nevertheless, how should you tackle a brand architecture issue? What is the best way forward?

Here’s five things to pay attention to:

Start with high-level vision, not tactical needs: Your organization has some idea of where its market is headed and what customers need now and in the near future. You simply cannot suggest any new level of marketing organization without first capturing and clarifying those assumptions.

[To be clear, brand architecture is an organizational challenge. There are two broad types of firms working in brand. Those guided by business and those driven by design. In our experience, firms with a strong design heritage tend to approach brand architecture through the doors of visual design rather than organizational necessity. Organizations approaching brand architecture through the design portal need to be wary of putting too much emphasis on the elegance of their structure over the necessity of getting folks on board with the change.]

The best way to get vision down is to individually consult top executives—especially leadership like the C-level and the Board—and then follow up by gathering them together around a whiteboard to resolve any differences and tease-out the long-term implications of the company’s vision.

If there is one thing we have noticed, few organizations take the time to think through the long-term impact of their world view. Be sure to ask leadership: how will our vision change the world? How will our customers change? What will they seek from us? What will happen internally? And what changes can we foresee internally?

Address buy-in at the outset. People drive change. Support, positive feelings, belief, motivation, optimism: all these things are essential. To drive organizational change you first need to understand what is working and what is not. And you need to catalog why people feel the way they do. Emotion plays a big part in getting teams on board with embracing the new. Making sure you hear from the right people, and that you have a sense of who listens to who, is a critical success factor in any company transformation.

If in doubt ask: who needs to buy into this idea? And how do we reach them? Why will they care?

Assemble the facts. Every team has its own version of organizational history. The freshest faces (an agency like us) arrive at the ball with their own ingrained ideas for how things should improve, often honed after hours of viewing rival websites and presentations. Or if you are especially lucky, informed by similar discussions with rival teams.

It’s easy to suggest new ways of looking at problems: we often tell underdogs they should think of themselves of leaders. Or remind the downtrodden that night is darkest before the dawn. Reframing how to approach a problem can be a vital first step.

But sooner of later you will need factual justification—a deep well of facts—to both convince colleagues to accept change and stay the course when it has been set. Thankfully, there is rarely a shortage of professional analysts and pundits in any growing industry. The trick is deciding who to listen to and how to fill in the gaps between what is known and what needs to be known. [To quote Donald Rumsfeld, the known knowns and the known unknowns are both critical].

Don’t forget to think in terms of qualitative and quantitative feedback. Logical types are rarely swayed by raw opinion—but are often putty when confronted by hard data in the form of surveys or well-researched reports. A handful of customer interviews—especially if presented in audio format (forgo the video—it’s rarely worth the effort and it is far easier to get customers to consent to recording a phone conversation)—can be extremely effective in swaying the Stubborn.

Once again: don’t skip a step! Make sure to dissect the research you conduct with your core team—and go out of your way to encourage spirited and energetic dialog. Don’t simply review the report and store the binder on the high shelf never to be reviewed again. (I have lost count of the orgs we have worked with that repeat the same basic exercise every few years without ever pausing to consider the-last-time-we-did-this. One Mortar client provided us with a catalog of four reports, each of which were commissioned by a previous marketing leader, and each of which studied essentially the same issue. They all reached broadly similar conclusions too. It appeared that no one had actually read the darn things).

Strive for simple. There are indeed a small handful of brand architecture models to consider. Consider them all. But remember the lesson of attempting to wrestle an octopus into a string bag: it’s easier if you cut the legs off. The simpler the answer the better. Simple is easy to understand. Simple is easier to communicate. Simple is easier to manage. Simple costs less. Simple stands the test of time. But simple is often not 100% possible. This is an organization-wide challenge after all, so pragmatic considerations can not always be avoided. Still, strive for simple, your colleagues will thank you.

Roll-out with a long-term plan. When we gathered the Mortar team to discuss what we had learned from our long careers in brand organization, one of the first things to rise to the top was the need to communicate the importance of how you communicate a new brand structure and how easy it is to bugger it up.

Brands don’t always take kindly to change. And the teams that are impacted will often grumble—unless you paint a motivating picture of the future that this new structure makes possible. And then ladder in how excited management is about the new direction. How the industry has been waiting for you to come to your senses and the new opportunities the changes will unlock. How you plan to watch over the rearranged family to ensure it is headed in the right direction and how you will handle unanticipated revisions. How much easier everyone’s job will be now and in the future. How bonuses will be tied to this change. And that we all need to get our act together because we are launching this new idea in a 30 days. A strong, confident, well thought through roll-out is essential for any organizational change.

So be sure to discuss the plan in detail with those that matter—and have plenty of ammo for those on the front-line of change.

We wouldn’t have our careers without the need to communicate about change constantly. Driving the new is the cross we chose when we got into Marketing. But never forget people are hard-wired to hate the new.

Remember that as you start your next day: for most ideas from Marketing are TROUBLE writ large.